How Your Brain Looks on Depression, Anxiety, and Mood Disorders, and How an Anti-Inflammatory Diet Can Help

Have you ever felt your mind slow down, your patience wear thin, or your motivation fade, even when life seems fine? You're not alone.

Modern research shows that mood, focus, and energy aren't just psychological; they're also biological. Your thoughts and emotions are deeply shaped by what happens in your body, especially through a process most of us never notice directly: inflammation.

Inflammation isn't inherently bad. It's your body's natural defense system, designed to protect and heal. But when stress, poor sleep, or an unbalanced diet keep it switched on, it begins to change how your brain works, how your neurons communicate, and how your emotions feel.

When Mood Meets Biology

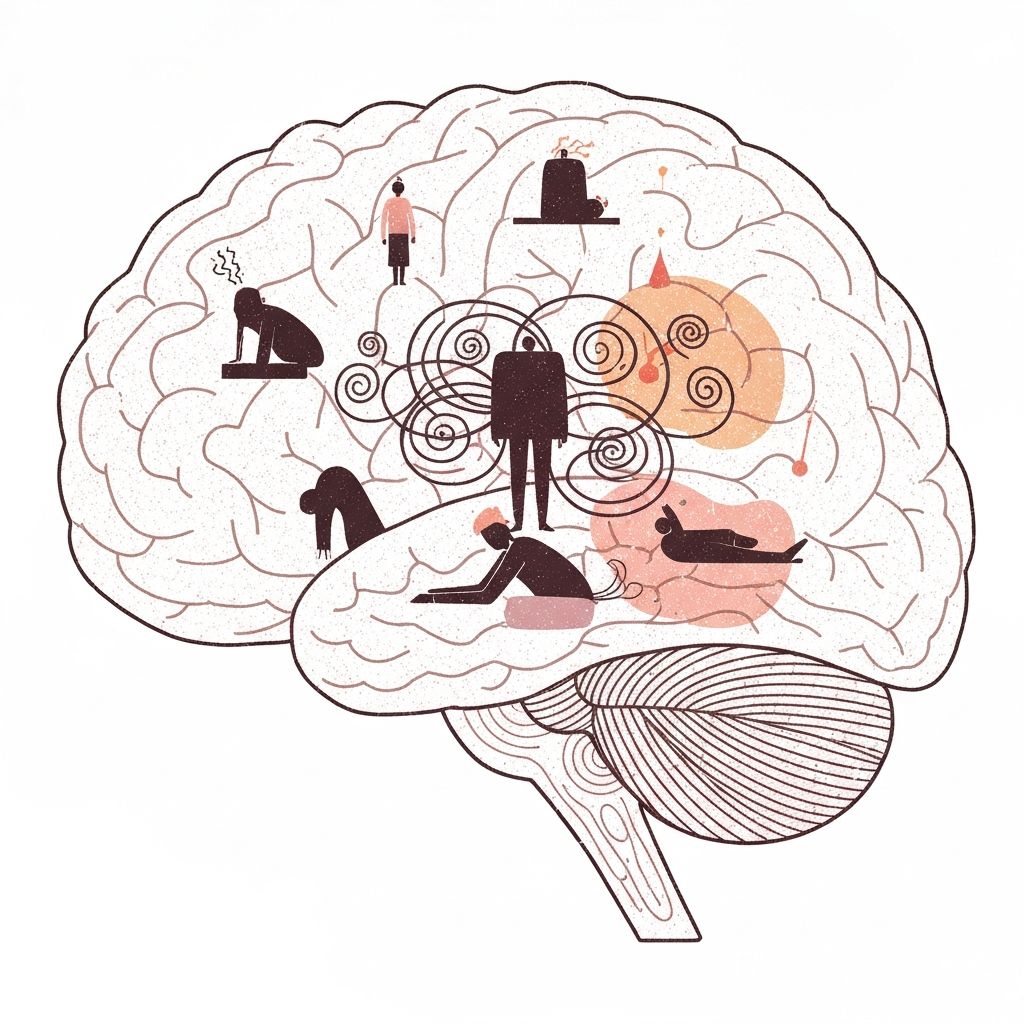

When depression or anxiety sets in, your brain doesn't simply "feel off." It functions differently. Inflammation is the invisible thread connecting low mood, chronic stress, and anxiety into a single loop that feeds itself.

Inflammation and Mood: When the Body's Fire Reaches the Mind

When inflammation lingers, your immune system releases signaling molecules called cytokines. In small doses, these molecules help your body heal from stress or infection. But when they stay active for too long, they can travel to the brain and disrupt neurotransmitters like serotonin, dopamine, and GABA — the chemistry that keeps you calm, focused, and balanced.

Research shows this biological link clearly. People with depression often have higher levels of interleukin-6 (IL-6), a cytokine that fuels inflammation, and C-reactive protein (CRP), a substance made by the liver in response to cytokines.

When these inflammatory signals stay elevated, many experience fatigue, irritability, and that sense of emotional heaviness that makes everything feel harder (Miller & Raison, 2016).

Stress and Brain Shrinkage: When Cortisol Takes Over

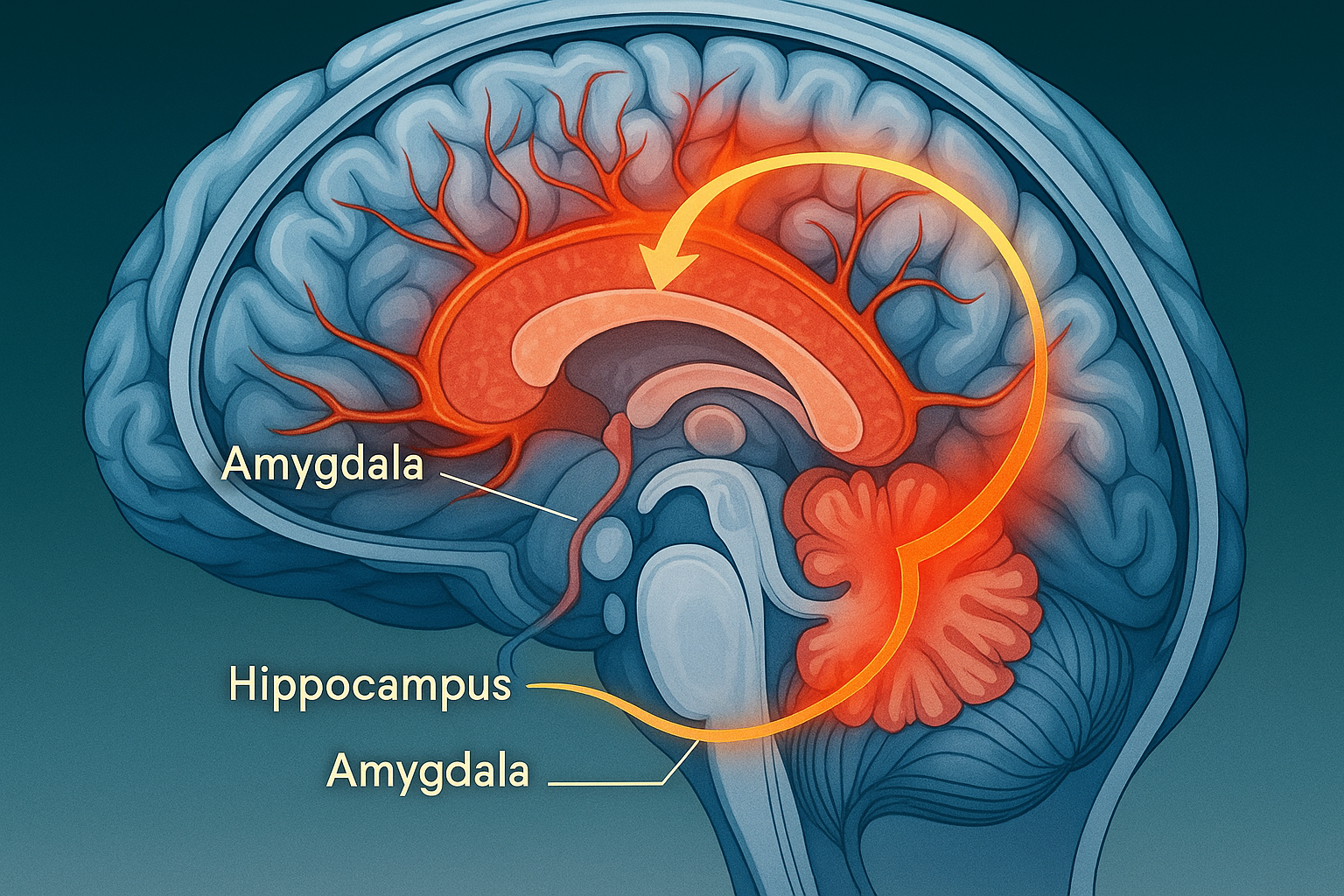

Cortisol is your main stress hormone. In small bursts, it sharpens focus and alertness. But when it stays elevated for too long, it begins to wear down the brain, particularly in the hippocampus, the region that regulates emotion, memory, and learning.

Brain imaging studies have shown that prolonged exposure to stress is linked to smaller hippocampal volume in people with depression (Videbech & Ravnkilde, 2004). As the hippocampus weakens, the brain struggles to switch off its stress response. The result is a mental loop where tension lingers long after the trigger has passed.

The Brain on Anxiety: When the Alarm Won't Turn Off

As the hippocampus loses strength, the amygdala, your brain's built-in alarm system, becomes more dominant. It starts scanning for threats even when none exist, amplifying small worries into intense emotional reactions.

Functional MRI studies reveal that this overactive amygdala response is common in generalized anxiety and social phobia (Etkin & Wager, 2007). This is why anxiety often feels like the mind has its foot on the accelerator with no brake in sight.

The Chemistry Shift: When the Brain's Wiring Changes

Inflammation doesn't only change which parts of the brain are active; it also affects how they communicate.

Under chronic stress, inflammation alters how your body processes tryptophan, an amino acid used to make serotonin, the neurotransmitter that helps you feel balanced and content. Instead of becoming serotonin, tryptophan gets diverted into the kynurenine pathway, producing compounds that can overstimulate or even damage brain cells (Wichers & Maes, 2004).

This biochemical shift creates a feedback loop: low serotonin makes you more anxious, which increases stress hormones, which in turn heightens inflammation.

The Big Picture: A Loop That Feeds Itself

What begins as inflammation in the body gradually affects the brain's structure, wiring, and chemistry. The hippocampus loses flexibility, the amygdala becomes overactive, and serotonin levels drop.

This is the biology of burnout, where the brain is constantly alert but never truly at rest.

The encouraging news is that this loop can be interrupted, and one of the most accessible ways to do so is through food.

How Food Calms the Fire

If inflammation can drive mood issues, then food can help cool it down. The anti-inflammatory diet isn't about restriction. It's about restoring balance and giving your brain what it needs to heal and perform well.

🌿 What to Eat More Of

| Group | Why It Helps |

|---|---|

| Fruits and Vegetables | Antioxidants reduce the impact of inflammation. |

| Omega-3 Fats (salmon, chia, walnuts) | Support neuron structure and reduce inflammatory chemicals. |

| Whole Grains and Legumes | Provide steady energy for stable mood and focus. |

| Fermented Foods (yogurt, kimchi) | Strengthen gut bacteria that influence serotonin production. |

| Spices (turmeric, ginger, garlic) | Contain compounds like curcumin and allicin that naturally calm inflammation. |

🚫 What to Ease Up On

| Category | Why |

|---|---|

| Processed foods and refined carbs | Trigger glucose spikes and inflammatory responses. |

| Excess sugar | Reduces brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which supports brain growth. |

| Trans fats | Linked to inflammation and cognitive decline. |

| Excess caffeine and alcohol | Disrupt hormone balance and sleep quality. |

What the Science Says

The evidence connecting diet and mood is strong and consistent.

In the SMILES Trial (Jacka et al., 2017), adults with depression who adopted a Mediterranean-style diet experienced greater mood improvements than those in a social support group.

In the SUN Project (Sánchez-Villegas et al., 2011), participants who ate more vegetables, olive oil, and fish had a lower risk of developing depression.

A large review published in Molecular Psychiatry (Lassale et al., 2019) found that diets rich in inflammatory foods were linked to a 35% higher risk of depression.

The takeaway is simple: food doesn't replace therapy or medication, but it creates the foundation for both to work better.

How Anti-Inflammatory Eating Heals the Brain

Eating an anti-inflammatory diet supports mental health in several ways:

- Reduces neuroinflammation, calming overactive circuits.

- Balances neurotransmitters, restoring serotonin and dopamine flow.

- Boosts BDNF (Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor), promoting neuron repair and growth.

- Restores gut–brain balance, improving emotional regulation.

What Is BDNF and Why It Matters

BDNF acts like fertilizer for your brain. It helps neurons grow, repair, and form new connections that support memory, focus, and resilience.

When stress, poor diet, or inflammation suppress BDNF, the brain becomes less adaptable and more prone to fatigue or low mood. But when you eat nutrient-rich, anti-inflammatory foods, BDNF levels rise, and your brain begins to recover.

In simple terms:

- High BDNF helps you think clearly and stay emotionally balanced.

- Low BDNF makes your mind feel stuck and easily overwhelmed.

🌱 A Simple Day of Anti-Inflammatory Eating for Experimentation

- Morning — Oats with berries, chia, and walnuts with matcha or green tea

- Lunch — Grilled salmon or tofu with quinoa, spinach, and olive oil

- Snack — Yogurt or kefir with flaxseed

- Dinner — Lentil stew with turmeric, garlic, and roasted vegetables

🌤️ The Takeaway

Your brain and body are constantly communicating. When inflammation runs high, that signal becomes distorted, leading to fatigue, mood swings, and anxiety.

When you eat to reduce inflammation, you quiet the noise and restore clarity.

Every meal is an opportunity to send your body a message: you are safe, nourished, and supported. 🌿

💚 How FuelMind Helps You Build This Connection

FuelMind was created to help you translate all this science into everyday awareness.

By scanning or logging your meals, FuelMind helps you notice how your diet affects your mood, energy, and focus. It reveals patterns you may not see on your own:

- Which foods help you stay focused and calm.

- Which meals leave you tired or restless.

- How your daily choices influence overall emotional balance.

References

Miller, A. H., & Raison, C. L. (2016). The role of inflammation in depression. Nature Reviews Immunology.

Videbech, P., & Ravnkilde, B. (2004). Hippocampal volume and depression. American Journal of Psychiatry.

Etkin, A., & Wager, T. D. (2007). Functional neuroimaging of anxiety. American Journal of Psychiatry.

Wichers, M., & Maes, M. (2004). The kynurenine pathway and depression. World Journal of Biological Psychiatry.

Jacka, F. N. et al. (2017). SMILES trial. BMC Medicine.

Sánchez-Villegas, A., et al. (2011). SUN Project. PLoS ONE.

Lassale, C., et al. (2019). Inflammatory potential of diet and depression risk. Molecular Psychiatry.